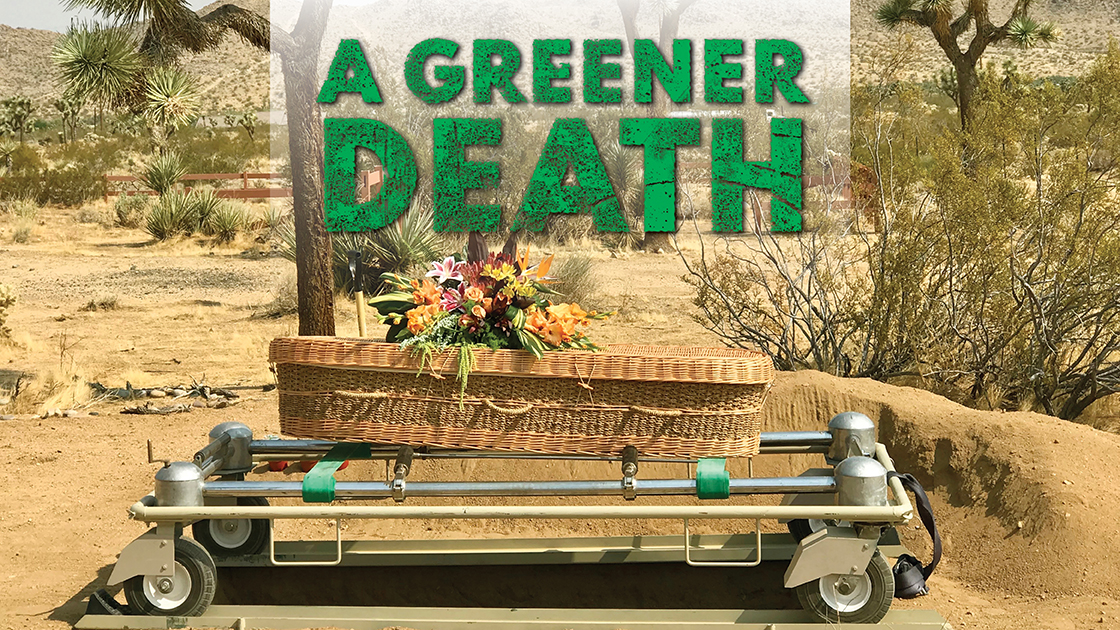

A Greener Death

More and more locals are joining the natural burial movement

Words by David A. Lee • Photos by Shawn O’Connor

With an ever-growing number of people seriously concerned about the current state of the environment, many readily embrace the notion of “going green” in life. They recycle, conserve water, compost, and rideshare, use public transportation, or drive hybrid or electric vehicles. But how many know it’s possible to go green in death?

On its website, the Green Burial Council (GBC) — a organization based in Placerville, California that focuses on alternative burial advocacy and education — defines the term as interment that cares for the dead “with minimal environmental impact that aids in the conservation of natural resources, reduction of carbon emissions, protection of worker health, and the restoration and/or preservation of habitat.”

“Green burial isn’t necessarily the top option for everybody, and that’s OK,” says GBC Board President Caitlyn Hauke, adding that misconceptions are often what keep people from choosing that path. “Are there going to be grave disturbances from animals? Is there going to be soil contamination from putting bodies [in the ground] without a casket? These are misunderstandings that we need to educate folks on.”

Indeed. Especially since conventional burials using caskets (made of wood or metal) enclosed inside concrete vaults in a cemetery still account for 35–40% of deaths in the United States today. In the “Disposition Statistics” portion of its website, GBC quotes Mary Woodsen of Cornell University and Greensprings Natural Preserve in Newfield, New York as saying that U.S. burials use approximately “4.3 million gallons embalming fluid (827,060 gallons of which is formaldehyde, methanol, and benzene), 20 million board feet of hardwoods (including rainforest woods), 1.6 million tons of concrete, 17,000 tons of copper and bronze, 64,500 tons of steel, [with] caskets and vaults leaching iron, copper, lead, zinc, and cobalt.”

When one factors in that this age-old custom forces funeral workers to wear personal protection equipment (PPE) to help shield them from toxic and cancer-causing chemicals, it’s obvious there’s nothing ecologically sound about this preference.

Palm Springs’ Wiefels Cremation and Funeral Services Pre-planning Director Kasey Scott offers green burial, along with many other more traditional services, to a wide array of clients. Wiefels owns Joshua Tree Memorial Park in the high desert, which facilitates 100% natural burials. “Which basically means that when you die, there is no embalming, there is no traditional casket, there is no vault,” she says. “Your body is either wrapped in a biodegradable shroud, or a biodegradable casket, and placed directly into the ground. And we hand dig the graves, so it is fully green.”

“Green burial … has the added bonus of being what many cultures have done with their dead for tens of thousands of years,” maintains Caitlin Doughty, a mortician, author, blogger, and influencer whose YouTube web series, “Ask a Mortician,” has almost two million subscribers. The founder of The Order of the Good Death, Doughty is one of the most vocal proponents of reforms to the Western funeral industry. Her trio of books — 2014’s “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory,” 2017’s “From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death,” and 2019’s “Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs? Big Questions from Tiny Mortals About Death” — are all New York Times best-sellers.

The interest in green burials has grown exponentially in the past 10 years, with more and more cemeteries accommodating the practice opening all the time. According to the website of the nonprofit New Hampshire Funeral Resources, Education & Advocacy, there are currently 386 certified green burial cemeteries in the U.S. and Canada.

Also encouraging: The 2022 Consumer Awareness and Preferences Report of The National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA) states that “60.5% would be interested in exploring green funeral options because of their potential environmental benefits, cost savings, or for some other reason, up from 55.7% in 2021.”

Scott reports that locally, more and more people are investigating this alternative, and that she firmly believes awareness will continue to grow as curiosity about it mounts.

For now, traditional cremation is by far still the most popular way of caring for human remains in the U.S. The NFDA claims the 2021 American [fire] cremation rate was 60% (and more than 70% in Canada), and is projected to reach 80% by 2035. Although environmentalists concede cremation is “better” than traditional burials, the process for each body nonetheless uses some 30 gallons of fossil fuel per cremation, releasing 140 pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and discharging dangerous amounts of mercury into the air if the deceased had mercury tooth fillings.

The greener alkaline hydrolysis (also known as aquamation, or water cremation) has been used since 1888, when it was developed in England to process animal carcasses. It’s been slowly gaining traction as replacement for casket/vault burial or traditional fire cremation. Available now in more than 50% of U.S. states — including all those on the West Coast, and locally in the Palm Springs area — the practice converts soft tissue into salt, amino acids, and sugars, and produces neither carbon emissions nor fossil fuels. The process destroys all DNA and RNA, and at its conclusion, the family receives remains similar to traditional cremation.

After studying the process of human decomposition, Katrina Spade founded Seattle’s Recompose, a company that composts human beings, a process officially known as natural organic reduction. “Microbes break the body and the plant materials down in about a month, cocooned in woodchips and straw,” Spade explains on the “Let’s Visit the Human Compositing Facility” episode of Doughty’s “Ask a Mortician.”

Adds Doughty: “As the body decays into soil, it changes on a molecular level, and pathogens, pharmaceuticals, and chemotherapy drugs are all neutralized in the process, reduced to well below what the EPA considers safe levels. After the 30 days, about one cubic yard of the nutrient-dense soil comes forth from the vessel. The soil is then allowed to cure before it can be used in gardens, forests, or conservation land.”

Natural organic reduction is now available in Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, and Vermont, with other states soon to come.

Matt O’Neill and Perri Peltz, director-producers of the popular and groundbreaking (pun unintended but unavoidable) HBO documentary “Alternate Endings: Six New Ways to Die in America,” offer myriad other creative ways of dealing with death, some greener than others. They include adding ashes to small concrete “sculptures” that help form artificial aquatic reefs, shooting cremains into space for those who always dreamed of eternity among the stars, and setting a body atop a funeral pyre to be ceremonially incinerated in a celebration of life before family and friends.

Another way to lessen the burden of death on the earth is

organ and/or body donation. DAP Health Manager of Home Care Supportive Services Becky Sandlin, who oversees nurses and social workers who visit patients and clients in their homes, says it’s not uncommon for the topic to come up with those in end-of-life hospice care. “It’s a heartwarming, selfless act to [donate one’s body to science] to help clinicians and

patients alike.”

Bimonthly magazine MIT Technology Review estimates that, “In the U.S., about 20,000 people or their families donate their bodies to scientific research and education each year. They do it because they want to make their deaths meaningful, or because they’re disenchanted with the traditional death industry.” Unused tissue and remains are cremated and returned to the family, along with information on how the body was purposed to further medical science.

Since the interest in going green in death shows no sign of slowing down, it’s promising that federal, state, and municipal laws that have historically prevented ecological burial options in the U.S. are continuously being challenged and changed — some after years of effort. As more and more Americans feel the need to leave a smaller footprint on this earth after they

die, green burials will surely prove to be the new interment

of choice.

As far as Scott sees it, the only way for one’s body to be disposed of in precisely the way one wishes is to look ahead. “I understand that people don’t want to talk about dying, or to plan for anything of that nature,” she says. “My job is to educate them as to why pre-planning is important. Then, if they want to move forward, it’s my honor to take care of them.”