The Benefits of Trauma-Informed Care

Sometimes, the question to ask isn’t just “What’s wrong with you?” but “What happened to you?”

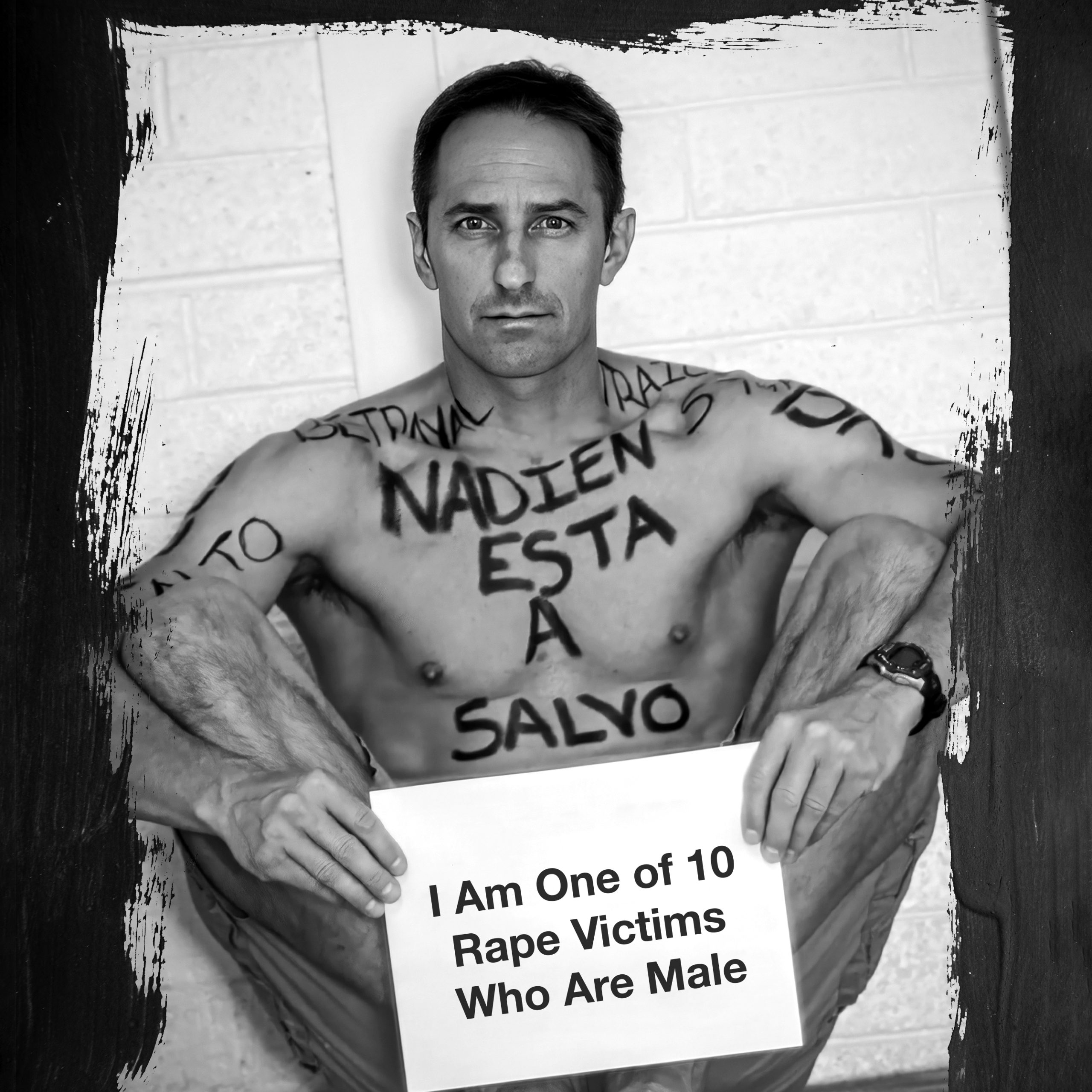

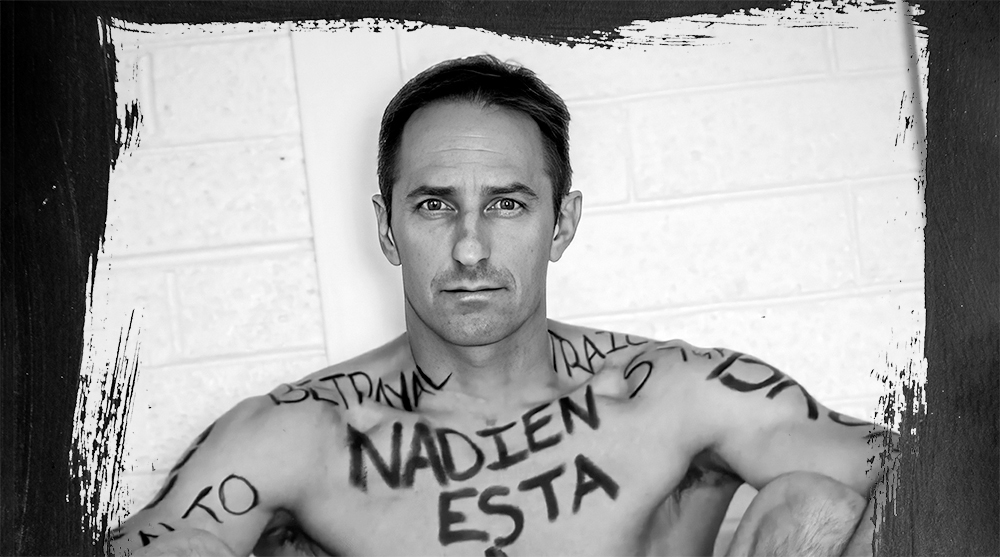

Words by Ron Blake • Photo by Rodrigo Izquierdo

As seen in DAP Health Magazine Issue 4

The admired, influential writer Maya Angelou said, “You can’t really know where you are going until you know where you have been.”

That is trauma-informed care — a way of treating patients by taking a holistic approach incorporating what has happened to them in the past. Where they’ve been, including the trauma. Bringing a more complete picture of their life to the medical professionals who work to heal them.

DAP Health recognizes that its medical professionals can’t truly help patients get healthy and happy until they explore beneath the surface to understand how trauma might have entered and affected each of their lives, often impacting how they respond to providers and treatment.

The nonprofit’s Dr. Jill Gover, clinical supervisor of its behavioral health internship program, is part of a team of licensed clinical psychologists who are warmly embracing this type of philosophy, with the expectation that it will bring about more positive health outcomes for patients while effectively managing care and costs, which in turn helps reduce staff burnout and turnover.

To quote another literary legend, the poet Robert Frost said, “The best way out is always through.” And that’s precisely what Dr. Gover and her colleagues are doing with DAP Health patients. They aren’t ignoring the traumas. They aren’t tiptoeing around them. They’re addressing them head-on. Using them as strengths — not as deficits or weaknesses — to move along the path to healing.

The Power of Lived Experience

The best way to more fully explain a concept like trauma-informed care is to go on an odyssey of empathy that shows the importance and necessity of it through a lived experience.

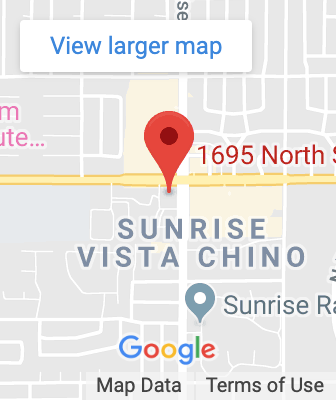

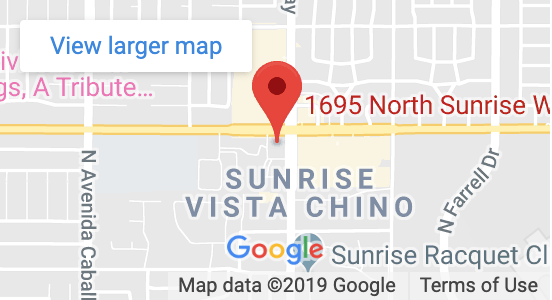

Last spring, I was in my local hospital’s emergency room in Phoenix, Arizona presenting with symptoms in my lower right leg that I thought were from a sports injury. The on-duty physician looked at my lower extremity and ordered an ultrasound to determine if it was a blood clot.

I was subsequently taken into a private room for that procedure. There, the male sonographer perfunctorily directed me to remove my shorts, socks, and shoes. I anxiously complied. He then began his duties, running a gel-covered device up and down the inside of my thigh. That’s when I flinched. My leg jerked away from the probing of his transducer. It felt like an instinctive response to danger. As it turns out, it really was — a fight or flight response normally exhibited in trauma.

In response to my reaction, the sonographer harshly said, “It’s not a big deal. You need to relax.” He was scolding me for not remaining still so that he could complete his work.

His flippant comment made that tense situation much worse. It awakened some bad memories for me. He had taken no time to learn anything about me as a person, nor about my history of trauma. Running that device up and down my inner thigh took me back to a horrific incident that happened on an inky dark, cold night 12 years ago, when I was 42. Three men entered my home while I was asleep. I was held down, beaten, and raped. I suffered serious injury that has required a dozen years of physical therapy, surgery, and counseling. Thanks to perseverance, I’m happy to say I’m still here.

We Must Avoid Retraumatizing Patients

To this hospital employee, the ultrasound was no big deal.

He performs these procedures routinely. I felt like just another statistic, and that this fellow was viewing it all from his perspective simply to finish his job. But for me, the touching of my inner thigh area triggered chilling, gruesome recollections.

After the ultrasound was completed, the sonographer pointed me back to a room to await the examination results. I started gathering my items into my backpack. All I wanted was to leave. I had been retraumatized. I had lost trust in this hospital. But before exiting the building, I made one phone call, to my retired family physician. We chatted, and I explained all that was occurring.

My former doctor said it sounded like it was a blood clot. He urged me to stay, wait for the results, and get treated if necessary. He knew all about my history, including that wickedly harrowing night long ago. I had trusted him for many years. I trusted him at this very moment. So, I stayed.

It’s a good thing I did. The ultrasound results came back.

It was a blood clot in my leg. Additional testing revealed the clot had spread maliciously throughout my lungs, presenting as pulmonary emboli. It was life-threatening. I was immediately transported to the intensive care unit for a four-day hospitalization.

Had it not been for that fortuitous phone call to my retired physician, who had been expertly trained in trauma-informed care, I would have gone home. Given how pervasive the spread of the clots had become, I quite possibly would have died in my sleep that night.

The Core Principles

I felt I could trust that longtime medical friend of mine. He knew me and my trauma. He made me feel safe. He collaborated with me and spoke with me as an equal. He did not allow any biases to interfere with our discussion. He empowered me and reminded me of the resilience I had to overcome obstacles. He spoke with me as a peer advocate — someone who has survived trauma as well.

My retired doctor used those six core principles of trauma-informed care in his engagement with me on that particular occasion. Trust. Safety. Collaboration. Removal of biases. Empowerment. Peer advocacy. Those are the very same principles DAP Health’s Dr. Gover and her colleagues use today. Every day.

The iconic novelist Ernest Hemingway said, “We are all broken, that’s how the light gets in.” DAP Health is dynamically combining that light and trauma-informed care to successfully guide patients to healing, health, and happiness.